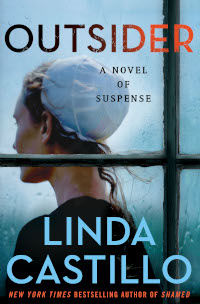

An instant New York Times bestseller

“A pulse-pounding Amish thriller (really!)

that’s all too relevant to our time.” —Kirkus Reviews (starred)

“[A] fast-paced, suspense-building ride, showing the character

development and sensitivity to the Amish culture that mark Castillo’s

masterful crime fiction.” –Booklist (starred)

EXCERPT

CHAPTER 1

The sleigh was an old thing. It had belonged to his grosseldre, who’d passed it down to his datt, who’d given it to him when he married nine years ago. Since, it had been used for everything from hauling hay, milk cans, and maple syrup buckets to carrying the sick calf that had been rejected by its mamm two springs ago. Last fall, Adam had replaced the runners, which cost him a pretty penny. Christmas three years ago, one of the shafts had broken, so he’d replaced both. There was still work to be done on the old contraption; the seat needed patching—or replacing—but the old shlay was functional enough that he and the children could get out and have some fun before the weather turned.

As he led Big Jimmy from his stall,

Adam Lengacher tried not to think about how much his life

had changed in the last two years. Nothing had been the same

since his wife, Leah, died. All of their lives had

changed—and not for the better. It was as if the heart of

the house had been sucked out and they were left grappling,

trying to fill some infinite space with something that had

never been theirs to begin with.

His Amish brethren had rallied in

the days and weeks afterward, as they always did in times of

tragedy. Some of the women still brought covered dishes and,

in summer, vegetables from their gardens for him and the

children. Bishop Troyer always made time to spend a few

extra minutes with him after worship. Some of the older

women had even begun their matchmaking shenanigans.

The thought made him shake his head—and smile. Life went on, he thought, as it should. The children had adjusted. Adam was comforted by the knowledge that when the time came, he would be with Leah again for all of eternity. Still, he missed her. He spent too much time thinking of her, too much time remembering, and wishing his children still had a mamm. He never talked about it, but he still hurt, too.

In the aisle, he lined up the old

draft horse, lifted the shafts, and backed the animal up to

the sleigh. He was in the process of buckling the leather

straps when his son Samuel ran into the barn.

“Datt! I can help!”

Adam tried not to smile as he rose

to his full height, walked around to the horse’s head, and

fastened the throat latch. His oldest child was the picture

of his mamm, with her exuberant personality and her gift of

chatter.

“Did you finish eating your

pancakes?” he asked.

“Ja.”

“You take all the eggs to the

house?”

“The brown ones, too. Annie broke

one.”

A whinny from the stall told them

their other draft horse, a mare they’d named Jenny, was

already missing her partner.

“We won’t keep him too long, Jenny!”

Sammy called out to the horse.

“Vo sinn die shveshtahs?” Adam

asked. Where are your sisters?

“Putting on their coats. Lizzie says

her shoes are too tight.”

Adam nodded. What did he know about

girls or their shoes? Nothing, he realized, a list that

seemed to grow with every passing day. “Why don’t you lead

Big Jimmy out of the barn?”

The boy squealed in delight as he

took the leather line in his small hand and addressed the

horse. “Kumma autseid, ald boo.” Come outside, old boy.

Adam watched boy and horse for a

moment. Sammy was just eight years old and already trying

hard to be a man. It was the one thing Adam could do, the

one thing he was good at, teaching his son what it meant to

be Amish, to live a humble life and submit to God. His two

daughters—Lizzie, who was barely seven, and Annie, who was

five—were another story altogether; Adam didn’t have a clue

how to raise girls.

He had a lot to be thankful for. His

children were healthy and happy; they kept his heart filled.

The farm kept his hands busy and earned him a decent living.

As Bishop Troyer had told him that first terrible week: The

Lord is close to the brokenhearted and saves those who are

crushed in spirit.

Adam had just closed the barn door

when his daughters ran down the sidewalk, their dresses

swishing about their legs. They were bundled up with scarves

and gloves, black winter bonnets covering their heads. This

morning, they would surely need the afghan Leah had knitted

to cover up with if they got cold.

“Samuel, help your sisters into the

shlay,” Adam said.

As the children boarded, Adam looked

around, assessing the weather. It had snowed most of the

night, and it was still falling at a good clip. The wind had

formed an enormous drift on the south side of the barn. Not

too bad yet, but he knew there was another round of snow

coming. By tonight, the temperature was supposed to drop

into the single digits. The wind was going to pick up, too.

According to his neighbor, Mr. Yoder, there was a blizzard

on the way.

When the children were loaded—the

girls in the backseat and Sammy next to him—Adam climbed in

and picked up the lines. “Kumma druff!” he said to the

horse. Come on there!

Big Jimmy might be a tad overweight

and a smidgen past his prime, but he loved the cold and snow

and this morning he came to life. Raising his head and tail,

the animal pranced through snow that reached nearly to his

knees, and within minutes the sled zoomed along the fence

line on the north side of the property.

“Look at Jimmy go!” cried Annie,

motioning toward the horse.

The sight of the old gelding warmed

Adam’s heart. “I think he’s showing off.”

“We’re going to have to give him

extra oats when we get home!” declared Lizzie.

“If Jimmy eats any more oats, we’re

going to have to pull him in the sleigh,” Adam told her.

At the sound of the children’s

laughter and the jangle of the harness, the bracing air

against his face, Adam felt some of the weight on his

shoulders lift. He took the sleigh north through the

cornfield, the tops of the cut stalks nearly obscured by a

foot or so of snow. The trees and branches sparkled white.

As they passed by the woods, he pointed out the ten-point

buck standing at the edge of the field. He showed them the

flock of geese huddled on the icy pond where the water had

long since frozen over. The beauty of the Ohio countryside

never ceased to boost his spirits, especially this morning

with the falling snow and the sound of his children’s

laughter in his ears.

On the north side of the property,

he turned right at the fence line and headed east toward

Painters Creek. It was too cold for them to stay out long.

Everyone had dressed warmly, but the wind cut right through

the layers. Already his fingers and face burned with cold.

Now that they’d moved past the tree line, he noticed the

dark clouds moving in from the northwest. He’d take the

sleigh to the county road and then cut south and go back

toward the house. Maybe have some hot chocolate before

afternoon chores, feeding the cows and hogs.

They’d only traveled another hundred

yards when Adam noticed the hump of a vehicle in the ditch.

The paint glinting through the layer of snow. It was an

unusual sight on this stretch of back road. There weren’t

many farms out this way and almost all of his neighbors were

Amish. As they neared the vehicle, he slowed the horse to a

walk.

“What’s that?” came Annie’s voice

from the back of the sleigh.

“Looks like an Englischer car,” said

Sammy.

“Maybe they got stuck in the snow,”

Lizzie suggested.

“Whoa.” Adam stopped the sleigh and looked around.

For a moment the only sounds came

from the puff of Jimmy’s breaths, the caw of a crow in the

woods to the east, and the clack of tree branches blowing in

the wind.

“You think there’s someone inside,

Datt?” asked Sammy.

“Only one way to find out.” Securing

the lines, Adam climbed down from the sleigh and started

toward the vehicle.

“Ich will’s sana!” Sammy started to

climb down. I want to see it.

“Stay with your sisters,” Adam told

his son.

From thirty feet away, he discerned

that the vehicle was actually a pickup truck, covered with

snow, nose-down in the ditch, the bumper against a big

hedge-apple tree. The impact had buckled the hood, causing

it to become unlatched. Evidently, the driver hadn’t been

able to see due to the heavy snow last night and must have

run off the road. From his vantage point, Adam couldn’t tell

if there was anyone inside. He waded through deep snow in

the ditch and made his way around to the driver’s side.

Surprise rippled through him when he saw that the door stood

open a few inches. Snow had blown onto the seat and floor.

Bending, he looked inside.

The airbag had deployed. A crack

split the front windshield, but the glass was still intact.

His gut tightened at the sight of the blood. There was a lot

of it. Too much, a little voice whispered. Adam didn’t know

anything about cars or trucks, but he didn’t think the

impact would have been violent enough to warrant so much

blood. What on earth had happened here?

Adam leaned into the vehicle for a

closer look, but there was nothing else of interest.

Straightening, he looked around. Any tracks left behind had

long since been filled in. Where had the driver gone?

He walked to the rear of the truck.

A tinge of apprehension tickled the back of his neck at the

sight of the bullet holes in the rear window. Six holes

connected by a mapwork of white cracks.

“Datt? Is someone in there?”

He startled at the sound of his

son’s voice. Turning, he saw the boy come up behind him,

hip-deep in snow, craning his neck to see into the vehicle.

“Go back to the sleigh, Sammy.”

But the boy had already spotted the

blood. “Oh.” His thin little brows drew together. “He’s

hurt, Datt, and needs help. Maybe we should look for him.”

The boy was right, of course.

Helping those in need was the Amish way. Still, the bullet

holes gave Adam pause. How had they gotten there and why?

“Let’s go back to the sleigh,” he

told his son.

Side by side, they struggled through

the ditch. Adam kept his eye out for tracks as they walked,

but there were none. Either someone had come by and picked

up the injured driver or he’d walked away and found help.

“Who is it, Datt?” asked Annie.

“No one there,” he told her.

“Are we going to look for him?”

Lizzie asked.

“We’ll look around a bit,” he said.

Sammy lowered his voice, as if to

avoid worrying his sisters. “Do you think he’s hurt, Datt?”

“Fleicht,” he said. Maybe.

Adam set his hand on his son’s head.

Such a sweet boy, so helpful and caring. But Adam didn’t

like seeing those bullet holes. He sure didn’t like seeing

all that blood. Even so, if someone was hurt, finding them

and helping them was the right thing to do.

“I’m going to look around,” he told

the children. “I want you to stay close to the sleigh. Call

out if you see anything. If we don’t find anyone here, we’ll

ride down to the freezer shanty over on Ithaca Road and use

the phone.”

“The Freezer” was a metal building

containing a dozen or so freezers the Amish rented to store

vegetables and meat. It had a community toilet, a hitching

post, and a phone.

Adam lifted his youngest daughter from the sleigh and looked around. The fence that ran alongside the road was a jumble of bent posts and sagging barbed wire. On the other side of the road, the woods grew thick all the way to Painters Creek.

“Be careful, children,” he said as

he started along the fence line. “Stay together and watch

out for deep drifts or else I’ll have to dig you out, too.”

His words were met with a spate of

giggles as they started toward the road.

Adam traversed the ditch and followed the fence. Fifty feet ahead, there was a knoll with a smattering of saplings and a place where blackberries flourished in late summer. He’d only gone twenty feet when he saw the scrap of fabric hanging from the barbed wire. Farther, a disturbance in the snow. At first, he thought maybe a deer had been hit and run into the ditch to die. But as he drew closer, he spotted the black leather of a boot. Blue denim.

He broke into a lurching run.

“Hello? Is someone there? Are you hurt?”

From ten feet away he recognized the

silhouette of a woman. Dark hair. A black leather coat and

boots. Blue jeans.

Adam reached her and knelt. She was

lying on her side, her head and shoulder against a fence

post. Her legs were pulled up nearly to her chest, as if

she’d been trying to stay warm. Brownish-black hair stuck

out from beneath a purple knit hat, covering much of her

face. Her clothes were caked with snow. Adam brushed the

hair away and was shocked when he found it frozen stiff. He

saw blue-tinged lips set into a face that was deathly pale.

She wore a scarf at the collar of her coat. A single leather

glove on her right hand. The other was bare and covered with

blood. Her skin was cold to the touch and for a terrible

moment he thought she was dead. Frozen to death.

Shaken by the thought, he worked off

one of his gloves, set his fingers against the back of her

neck, beneath her hat and hair. Warm, he realized. Still

alive.

Relieved, he looked around. The

closest house was his own. The Yoder farm was another mile

down the road. The snow was coming down so hard he couldn’t

even see the roof of their barn. They were Amish and didn’t

have a phone, anyway. The closest Amish pay phone was at the

freezer shanty, which was in the opposite direction.

He craned his neck right, spotted

Lizzie and Annie using sticks to play tic-tac-toe in the

snow. Sammy had made his way twenty yards ahead, checking

the area along the fence.

The woman moaned. Adam turned back

to her to see her twist. She raised her head and squinted at

him. She was staring at his hat, her eyes wide. Her face was

a mask of confusion and pain. “Get the fuck away from me,”

she slurred.

He didn’t know what to say to that.

He was trying to help her. Was she confused? He’d seen it

happen, like the time he’d been hunting and his cousin fell

through the ice. By the time they arrived home, his cousin

hadn’t even been able to speak.

“Don’t be afraid.” Raising his

hands, he sat back on his haunches. “I’m going to help you.”

“Back off.” She raised her left hand

as if to fend him off. “I mean it.”

“You were in an accident,” he told

her. “You’re bleeding. You need a doctor.”

“No doctor.” She tried to scoot

backward, as if to put some distance between them, but ended

up flopping sideways. Her face hit the snow. There were ice

crystals on her skin. A smear of blood on her cheek.

Propping herself up on one elbow, she reached beneath her

coat with her right hand and pulled out a pistol.

“Keep your fucking distance,” she

hissed. “Stay back.”

Adam lurched away, raised his hands.

“I have children.”

She raised her other hand, fingers

blue with cold and covered with blood. She looked at it as

if she wasn’t sure it was hers, wiped her face. “Who are

you?”

“Adam … Lengacher.”

She blinked at him. “Where am I?”

“Painters Mill.”

Out of the corner of his eye, he

ascertained the location of his children. They were ten

yards away, near the fence. Too close. If this woman was

narrisch—crazy—and fired that gun, there would be no

protecting them.

Adam scooched back another foot,

kept his hands raised. “I’m leaving. Just stay calm and

we’ll go. Okay?”

“It’s a lady.”

His heart gave a single hard thud at

the sound of his son’s voice. He hadn’t heard him approach.

He twisted around fast and made eye contact with him. “Gay

zu da shlay, Samuel. Nau.” Go to the sleigh. Now.

The boy’s eyes widened at his datt’s

tone. He took a step back. “What’s wrong?”

“Gay,” he said. “Nau.” Go. Now.

The boy walked backward, frightened.

Adam turned back to the woman. She was looking at Sammy.

Gripping the pistol as if it were her lifeline. Dear God,

what had he stumbled upon?

Before he could ponder the question,

the hand holding the pistol collapsed as if she no longer

had the strength to keep her arm outstretched. The gun slid

from her palm. Her body went slack and she settled more

deeply into the snow. She stared at him for a moment and

then closed her eyes.

“I’m spent,” she rasped.

Adam wasn’t sure how to respond. The

one thing he did know was that he didn’t want her reaching

for that gun again. Moving closer, he picked it up. The

steel was cold in his palm, wet from the snow, bits of ice

on the muzzle. Not a revolver. He was no stranger to rifles;

he’d been a hunter since he was thirteen years old. He had a

.22 and an old muzzle-loader at home. This was … something

else. What was she doing with a gun? Was it for protection?

Was she a trustworthy individual? A criminal? If he helped

her would he bring danger into his home?

Keeping the weapon out of sight from

the children, Adam turned it over in his hand. It took him a

moment, but he figured out how to release the magazine that

held the ammunition. He dropped the clip into his coat

pocket. He pulled back the slide, checked the chamber,

dumped the single bullet into the snow. He put the weapon in

another coat pocket.

“I guess I’m at your mercy now,

huh?” the woman whispered.

Adam got to his feet. A glance over

his shoulder told him all three children were sitting in the

sleigh, their faces turned his way, expressions curious and

worried. Around him the day no longer seemed magical. The

snow no longer a gentle thing, but a threat. The wind had

picked up, driving the falling snow sideways. Even the horse

was hunched against the cold and wind.

He looked down at the woman. She lay

still, unmoving, her eyes closed, as if she’d given up.

Already a thin veil of snow clung to the newly exposed area

of her clothes, her hair. If he left her here, she would

freeze to death—or become buried if the sheriff’s deputies

couldn’t get to her quickly.

She shifted as if in pain, made a

sound that might have been a word. Keeping his distance,

Adam knelt. “Do you want me to help you?” he asked.

She didn’t open her eyes. Her lips

barely moved when she spoke. “Get Kate Burkholder,” she

ground out. “I’m a cop. Get her.”

Adam knew the name. He’d known Katie

Burkholder most of his life. How did this stranger know her?

This was not the time to question her. She was injured and

weak. He looked at his children. “Make a place for her on

the backseat!” he called out. “We’re taking her home.”

“Ja!” Sammy said.

Adam looked at the woman. “Can you

walk?”

She shifted, winced, her left leg

flailing and then going still. “I don’t know. Give me a

minute.”

He didn’t think a minute would help.

In fact, if she didn’t get out of the cold soon, she’d

likely fall to unconsciousness and die.

“I’ll help you.” Not giving himself

time to debate further, he bent to her, plunged his hands

into the snow beneath her, and scooped her into his arms.

She was small, smelled of cold air and some sweet

English-woman scent.

“Sammy!” he said. “Take the lines.

We’re going home.”

The woman’s head lolled; she was

dead weight in his arms. Concern for her niggled at the back

of his mind when he saw blood on her coat. He felt the

warmth of it run across his wrist as he trudged through deep

snow.

“An Englischer,” Sammy said as Adam

approached the sleigh.

“Ja,” he replied.

“Is she frozen?” the boy asked.

“Hurt. And weak from the cold.”

“Who is it, Datt?” came Lizzie’s

voice.

“I don’t know,” he told her. “Must

have gotten lost in the storm. Someone’s probably worried

about her, though, don’t you think?”

“Her mamm probably,” Lizzie said.

“They always worry.”

“Annie, get the afghan so we can

cover her up. Quickly now.”

“Datt, she’s bleeding!” Sammy

pointed, alarm ringing in his voice, his little hands

gripping the leather lines.

“She must have hurt herself in the

wreck is all,” Adam told him. “Come on now. Girls, move to

the front seat. Give her some room.”

Lizzie and Annie scrambled into the

front. Adam stepped into the sleigh and set the woman on the

rear bench seat, trying to ignore the smear of blood on the

leather. The seat wasn’t long enough for her to stretch out,

so he bent her legs at the knee.

“Hand me that afghan,” he said.

Annie thrust the throw at him. “She

looks cold.”

“I think she’s been out here

awhile,” he said. “Too long.”

“Is she going to die?” Lizzie asked.

Since losing their mother, the

children had become aware of death and all its shadowy

facets. Adam did his best to answer their questions. They

knew death was part of the life cycle. They knew that when

people died, they went to heaven to spend all of eternity

with God. But they also knew that death had taken their mamm

from them and she wouldn’t be coming back.

“That’s up to God now, isn’t it?”

Adam draped the afghan over the woman, tucking it beneath

her. “We will help her as best we can. The rest is up to

Him.”

He worked off his coat and draped it

over the woman. Under different circumstances, he would have

taken the lines and asked one of the children to stay with

her. In light of the gun and her rough language, he didn’t

want them getting too close to her.

Kneeling on the floor between the

front seatback and the rear seat, he set his hand on his

son’s shoulder.

“Let’s go,” he said.

Copyright © 2020 by Linda Castillo

Home