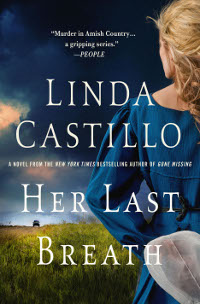

Critical Acclaim for HER LAST BREATH

“Castillo's fifth Amish thriller featuring Painters Mill, Ohio, police chief Katie Burkholder is a stunner."--Publisher's Weekly [starred review]

“Kate Burkholder is the heart of Castillo's masterful series . . . This compelling mystery combines increasing nuance and complexity with heart-stopping action."--Booklist [starred review]

"In her fifth installment, Castillo combines the simple Amish lifestyle with dizzying hairpin twists and turns, and the result is a mind-blowing read that will keep her fans and mystery readers engrossed."--Library Journal

"Castillo, whose skill at creating a shocking story is amplified by her talent for rich characterization, invests her work with intellignece and love. And Her Last Breath will leave readers gasping."--Richmond Times-Dispatch

Finalist for the International Thriller Writers 2014 Best Hardcover thriller award

Excerpt of HER LAST BREATH

CHAPTER 1

When it rains,

it pours. Those words were one of my mamm's favorite maxims

when I was growing up. As a child, I didn't understand its

true meaning, and I didn't spend much time trying to figure

it out. In the eyes of the Amish girl I'd been, more was

almost always a good thing. The world around me was a

swiftly moving river, chock-full of white-water rapids and

deep holes filled with secrets I couldn't fathom. I was

ravenous to raft that river, anxious to dive into all of

those dark crevices and unravel their closely guarded

secrets. It wasn't until I entered my twenties that I

realized there were times when that river overflowed its

banks and a killing flood ensued.

My mamm is gone now

and I haven't been Amish for fifteen years, but I often find

myself using that old adage, particularly when it comes to

police work and, oftentimes, my life.

I've been on

duty since 3:00 P.M. and my police radio has been eerily

quiet for a Friday, not only in Painters Mill proper, but

the entirety of Holmes County. I made one stop and issued a

speeding citation, mainly because it was a repeat offense

and the eighteen-year-old driver is going to end up killing

someone if he doesn't slow down. I've spent the last hour

cruising the backstreets, trying not to dwell on anything

too serious, namely a state law enforcement agent by the

name of John Tomasetti and a relationship that's become a

lot more complicated than I ever intended.

We met

during the Slaughterhouse Murders investigation almost two

years ago. It was a horrific case: A serial killer had

staked his claim in Painters Mill, leaving a score of dead

in his wake. Tomasetti, an agent with the Ohio Bureau of

Identification and Investigation, was sent here to assist.

The situation was made worse by my personal involvement in

the case. They were the worst circumstances imaginable,

especially for the start of a relationship, professional or

otherwise. Somehow, what could have become a debacle of

biblical proportion, grew into something fresh and good and

completely unexpected. We're still trying to figure out how

to define this bond we've created between us. I think he's

doing a better job of it than I am.

That's the thing

about relationships; no matter how hard you try to keep

things simple, all of those gnarly complexities have a way

of seeping into the mix. Tomasetti and I have arrived at a

crossroads of sorts, and I sense change on the wind. Of

course, change isn't always a negative. But it's rarely

easy. The indecision can eat at you, especially when you've

arrived at an important junction and you're not sure which

way to go—and you know in your heart that each path will

take you in a vastly different direction.

I'm not

doing a very good job of keeping my troubles at bay, and I

find myself falling back into another old habit I acquired

from my days on patrol: wishing for a little chaos. A bar

fight would do. Or maybe a domestic dispute. Sans serious

injury, of course. I don't know what it says about me that

I'd rather face off with a couple of pissed-off drunks than

look too hard at the things going on in my own life.

I've just pulled into the parking lot of LaDonna's Diner for

a BLT and a cup of dark roast to go when the voice of my

second shift dispatcher cracks over the radio.

"Six

two three."

I pick up my mike. "What do you have,

Jodie?"

"Chief, I just took a nine one one from Andy

Welbaum. He says there's a bad wreck on Delisle Road at CR

14."

"Anyone hurt?" Dinner forgotten, I glance in my

rearview mirror and make a U-turn in the gravel lot.

"There's a buggy involved. He says it's bad."

"Get an

ambulance out there. Notify Holmes County." Cursing, I make

a left on Main, hit my emergency lights and siren. The

engine groans as I crank the speedometer up to fifty. "I'm

ten seventy-six."

I'm doing sixty by the time I leave the corporation limit of

Painters Mill. Within seconds, the radio lights up as the

call goes out to the Holmes County sheriff's office. I make

a left on Delisle Road, a twisty stretch of asphalt that

cuts through thick woods. It's a scenic drive during the

day, but treacherous as hell at night, especially with so

many deer in the area.

County Road 14 intersects a

mile down the road. The Explorer's engine groans as I crank

the speedometer to seventy. Mailboxes and the black trunks

of trees fly by outside my window. I crest a hill and spot

the headlights of a single vehicle ahead. No ambulance or

sheriff's cruiser yet; I'm first on scene.

I'm twenty

yards from the intersection when I recognize Andy Welbaum's

pickup truck. He lives a few miles from here. Probably

coming home from work at the plant in Millersburg. The truck

is parked at a haphazard angle on the shoulder, as if he

came to an abrupt and unexpected stop. The headlights are

trained on what looks like the shattered remains of a

four-wheeled buggy. There's no horse in sight; either it ran

home or it's down. Judging from the condition of the buggy,

I'm betting on the latter.

"Shit." I brake hard. My

tires skid on the gravel shoulder. Leaving my emergency

lights flashing, I hit my high beams for light and jam the

Explorer into park. Quickly, I grab a couple of flares from

the back, snatch up my Maglite, and then I'm out of the

vehicle. Snapping open the flares, I scatter them on the

road to alert oncoming traffic. Then I start toward the

buggy.

My senses go into hyperalert as I approach,

several details striking me at once. A sorrel horse lies on

its side on the southwest corner of the intersection, still

harnessed but unmoving. Thirty feet away, a badly damaged

buggy has been flipped onto its side. It's been broken in

half, but it's not a clean break. I see splintered wood, two

missing wheels, and a ten-yard-wide swath of debris—pieces

of fiberglass and wood scattered about. I take in other

details, too. A child's shoe. A flat-brimmed hat lying amid

brown grass and dried leaves …

My mind registers all

of this in a fraction of a second, and I know it's going to

be bad. Worse than bad. It will be a miracle if anyone

survived.

I'm midway to the buggy when I spot the

first casualty. It's a child, I realize, and everything

grinds to a halt, as if someone threw a switch inside my

head and the world winds down into slow motion.

"Fuck. Fuck." I rush to the victim, drop to my knees. It's a

little girl. Six or seven years old. She's wearing a blue

dress. Her kapp is askew and soaked with blood and I think:

head injury.

"Sweetheart." The word comes out as a

strangled whisper.

The child lies in a supine

position with her arms splayed. Her pudgy hands are open and

relaxed. Her face is so serene she might have been sleeping.

But her skin is gray. Blue lips are open, revealing tiny

baby teeth. Already her eyes are cloudy and unfocused. I see

bare feet and I realize the force of the impact tore off her

shoes.

Working on autopilot, I hit my lapel mike, put

out the call for a 10-50F. A fatality accident. I stand,

aware that my legs are shaking. My stomach seesaws, and I

swallow something that tastes like vinegar. Around me, the

night is so quiet I hear the ticking of the truck's engine a

few yards away. Even the crickets and night birds have gone

silent as if in reverence to the violence that transpired

here scant minutes before.

Insects fly in the beams

of the headlights. In the periphery of my thoughts, I'm

aware of someone crying. I shine my beam in the direction of

the sound, and spot Andy Welbaum sitting on the ground near

the truck with his face in his hands, sobbing. His chest

heaves, and sounds I barely recognize as human emanate from

his mouth.

I call out to him. "Andy, are you hurt?"

He looks up

at me, as if wondering why I would ask him such a thing.

"No."

"How many in the buggy? Did you check?" I'm on

my feet and looking around for more passengers, when I spot

another victim.

I don't hear Andy's response as I

start toward the Amish man lying on the grassy shoulder.

He's in a prone position with his head turned to one side.

He's wearing a black coat and dark trousers. I try not to

look at the ocean of blood that has soaked into the grass

around him or the way his left leg is twisted with the foot

pointing in the wrong direction. He's conscious and watches

me approach with one eye.

I kneel at his side.

"Everything's going to be okay," I tell him. "You've been in

an accident. I'm here to help you."

His mouth opens.

His lips quiver. His full beard tells me he's married, and I

wonder if his wife is lying somewhere nearby.

I set

my hand on his. Cold flesh beneath my fingertips. "How many

other people on board the buggy?"

"Three … children."

Something inside me sinks. I don't want to find any more

dead children. I pat his hand. "Help is on the way."

His gaze meets mine. "Katie…"

The sound of my name

coming from that bloody mouth shocks me. I know that voice.

That face. Recognition impacts me solidly. It's been years,

but there are some things—some people—you never forget. Paul

Borntrager is one of them. "Paul." Even as I say his name, I

steel myself against the emotional force of it.

He

tries to speak, but ends up spitting blood. I see more on

his teeth. But it's his eye that's so damn difficult to look

at. One is gone completely; the other is cognizant and

filled with pain. I know the person trapped inside that

broken body. I know his wife. I know at least one of his

kids is dead, and I'm terrified he'll see that awful truth

in my face.

"Don't try to talk," I tell him. "I'm

going to check the children."

Tears fill his eye. I

feel his stare burning into me as I rise and move away.

Quickly, I sweep my beam along the ground, looking for

victims. I'm aware of sirens in the distance and relief

slips through me that help is on the way. I know it's a

cowardly response, but I don't want to deal with this alone.

I think of Paul's wife, Mattie. A lifetime ago, she was

my best friend. We haven't spoken in twenty years; she may

be a stranger to me now, but I honestly don't think I could

bear it if she died here tonight.

Mud sucks at my

boots as I cross the ditch. On the other side, I spot a tiny

figure curled against the massive trunk of a maple tree. A

boy of about four years of age. He looks like a little doll,

small and vulnerable and fragile. Hope jumps through me when

I see steam rising into the cold night air. At first, I

think it's vapor from his breath. But as I draw closer I

realize with a burgeoning sense of horror that it's not a

sign of life, but death. He's bled out and the steam is

coming from the blood as it cools.

I go to him

anyway, kneel at his side, and all I can think when I look

at his battered face is that this should never happen to a

child. His eyes and mouth are open. A wound the size of my

fist has peeled back the flesh on one side of his head.

Sickened, I close my eyes. "Goddammit," I choke as I get

to my feet.

I stand there for a moment, surrounded by

the dead and dying, overwhelmed, repulsed by the bloodshed,

and filled with impotent anger because this kind of carnage

shouldn't happen and yet it has, in my town, on my watch,

and there's not a damn thing I can do to save any of them.

Trying hard to step back into myself and do my job, I

run my beam around the scene. A breeze rattles the tree

branches above me and a smattering of leaves float down.

Fingers of fog rise within the thick underbrush and I find

myself thinking of souls leaving bodies.

A whimper yanks me from my stasis. I spin, jerk my beam

left. I see something tangled against the tumbling wire

fence that runs along the tree line. Another child. I break

into a run. From twenty feet away I see it's a boy. Eight or

nine years old. Hope surges inside me when I hear him groan.

It's a pitiful sound that echoes through me like the

electric pain of a broken bone. But it's a good sound, too,

because it tells me he's alive.

I drop to my knees at

his side, set my flashlight on the ground beside me. The

child is lying on his side with his left arm stretched over

his head and twisted at a terrible angle. Dislocated

shoulder, I think. Broken arm, maybe. Survivable, but I've

worked enough accidents to know it's usually the injuries

you can't see that end up being the worst.

One side

of his face is visible. His eyes are open; I can see the

curl of lashes against his cheek as he blinks. Flecks of

blood cover his chin and throat and the front of his coat.

There's blood on his face, but I don't know where it's

coming from; I can't pinpoint the source.

Tentatively, I reach out and run my fingertips over the top

of his hand, hoping the contact will comfort him. "Honey,

can you hear me?"

He moans. I hear his breaths

rushing in and out between clenched teeth. He's breathing

hard. Hyperventilating. His hand twitches beneath mine and

he cries out.

"Don't try to move, sweetie," I say.

"You were in an accident, but you're going to be okay." As I

speak, I try to put myself in his shoes, conjure words that

will comfort him. "My name's Katie. I'm here to help you.

Your datt's okay. And the doctor is coming. Just be still

and try to relax for me, okay?"

His small body

heaves. He chokes out a sound and flecks of blood spew from

his mouth. I hear gurgling in his chest, and close my eyes

tightly, fighting to stay calm. Don't you dare take this

one, too, a little voice inside my head snaps.

The

urge to gather him into my arms and pull him from the fence

in which he's tangled is powerful. But I know better than to

move an accident victim. If he sustained a head or spinal

injury, moving him could cause even more damage. Or kill

him.

The boy stares straight ahead, blinking. Still

breathing hard. Chest rattling. He doesn't move, doesn't try

to look at me. "… Sampson…" he whispers.

I don't know

who that is; I'm not even sure I heard him right or if he's

cognizant and knows what he's saying. It doesn't matter. I

rub my thumb over the top of his hand. "Shhh." I lean close.

"Don't try to talk."

He shifts slightly, turns his

head. His eyes find mine. They're gray. Like Mattie's, I

realize. In their depths I see fear and the kind of pain no

child should ever have to bear. His lips tremble. Tears

stream from his eyes. "Hurts…"

"Everything's going to

be okay." I force a smile, but my lips feel like barbed

wire.

A faint smile touches his mouth and then his

expression goes slack. Beneath my hand, I feel his body

relax. His stare goes vacant.

"Hey." I squeeze his

hand, willing him not to slip away. "Stay with me, buddy."

He doesn't answer.

The sirens are closer now. I

hear the rumble of the diesel engine as a fire truck arrives

on scene. The hiss of tires against the wet pavement as more

vehicles pull onto the shoulder. The shouts of the first

responders as they disembark.

"Over here!" I yell.

"I've got an injured child!"

I stay with the boy

until the first paramedic comes up behind me. "We'll take it

from here, Chief."

He's about my age, with a crew cut

and blue jacket inscribed with the Holmes County Rescue

insignia. He looks competent and well trained, with a trauma

kit slung over his shoulder and a cervical collar beneath

his arm.

"He was conscious a minute ago," I tell the paramedic.

"We'll take good care of him, Chief."

Rising, I

take a step back to get out of the way.

He kneels at

the child's side. "I need a backboard over here!" he shouts

over his shoulder.

Close on his heels, a young

firefighter snaps open a reflective thermal blanket and goes

around to the other side of the boy. A third paramedic trots

through the ditch with a bright yellow backboard in tow.

I leave them to their work and hit my lapel mike.

"Jodie, can you ten seventy-nine?" Notify coroner.

"Roger that."

I glance over my shoulder to the place

where I left Paul Borntrager. A firefighter kneels at his

side, assessing him. I can't see the Amish man's face, but

he's not moving.

Firefighters and paramedics swarm

the area, treating the injured and looking for more victims.

Any cop that has ever worked patrol knows that passengers

who don't utilize safety belts—which is always the case with

a buggy—can be ejected a long distance, especially if speed

is a factor. When I was a rookie in Columbus, I worked an

accident in which a semi truck went off the road and flipped

end over end down a one-hundred-foot ravine. The driver,

who'd been belted in, was seriously injured, but survived.

His wife, who hadn't been wearing her safety belt, was

ejected over two hundred feet. The officers on scene—me

included—didn't find her for nearly twenty minutes.

Afterward, the coroner told me that if we'd gotten to her

sooner, she might have survived. Nobody ever talked about

that accident again. But it stayed with me, and I never

forgot the lesson it taught.

Wondering if Mattie was

a passenger, I establish a mental grid of the scene.

Starting at the point of impact, I walk the area, looking

for casualties, working my way outward in all directions. I

don't find any more victims.

When I'm finished, I

drift back to where I left Paul, expecting to find him being

loaded onto a litter. I'm shocked to see a blue tarp draped

over his body, rain tapping against it, and I realize he's

died.

I know better than to let this get to me. I

haven't talked to Paul or Mattie in years. But I feel

something ugly and unwieldy building inside me. Anger at the

driver responsible. Grief because Paul is dead and Mattie

must be told. The pain of knowing I'll probably be the one

to do it.

"Oh, Mattie," I whisper.

A lifetime

ago, we were inseparable—more like sisters than friends. We

shared first crushes, first "singings," and our first

heartbreaks. Mattie was there for me during the summer of my

fourteenth year when an Amish man named Daniel Lapp

introduced me to violence. My life was irrevocably changed

that day, but our friendship remained a constant. When I

turned eighteen and made the decision to leave the Plain

Life, Mattie was one of the few who supported me, even

though she knew it would mean the end of our friendship.

We lost touch after I left Painters Mill. Our lives took

different paths and never crossed again. I went on to

complete my education and become a police officer. Mattie

joined the church, married Paul, and started a family. For

years, we've been little more than acquaintances, rarely

sharing anything more than a wave on the street. But I never

forgot those formative years, when summer lasted forever,

the future held infinite promise—and we still believed in

dreams.

Dreams that, for one of us, ended tonight.

I walk to Andy Welbaum's truck. It's an older Dodge with

patches of rust on the hood. A crease on the rear quarter

panel. Starting with the front bumper, I circle the vehicle,

checking for damage. But there's nothing there. Only then do

I realize this truck wasn't involved in the accident.

I find Andy leaning against the front bumper of a nearby

Holmes County ambulance. Someone has given him a slicker.

He's no longer crying, but he's shaking beneath the yellow

vinyl.

He looks at me when I approach. He's about forty years old

and balding, with circles the size of plums beneath hound

dog eyes. "That kid going to be okay?" he asks.

"I

don't know." The words come out sounding bitchy, and I take

a moment to rein in my emotions. "What happened?"

"I

was coming home from work like I always do. Slowed down to

turn onto the county road and saw all that busted-up wood

and stuff scattered all over the place. I got out to see

what happened…" Shaking his head, he looks down at his feet.

"Chief Burkholder, I swear to God I ain't never seen

anything like that before in my life. All them kids. Damn."

He looks like he's going to start crying again. "Poor

family.”

"So your vehicle wasn't involved in the

accident?"

"No ma'am. It had already happened when I

got here."

"Did you witness it?"

"No." He

looks at me, grimaces. "I think it musta just happened

though. I swear to God the dust was still flying when I

pulled up."

"Did you see any other vehicles?"

"No." He says the word with some heat. "I suspect that

sumbitch hightailed it."

"What happened next?"

"I called nine one one. Then I went over to see if I

could help any of them. I was a medic in the Army way back,

you know." He falls silent, looks down at the ground. "There

was nothing I could do."

I nod, struggling to keep a

handle on my outrage. I'm pissed because someone killed

three people—two of whom were children—injured a third, and

left the scene without bothering to render aid or even call

for help.

I let out a sigh. "I'm sorry I snapped at

you."

"I don't blame you. I don't see how you cops

deal with stuff like this day in and day out. I hope you

find the bastard that done it."

"I'm going to need a

statement from you. Can you hang around for a little while

longer?"

"You bet. I'll stay as long as you need me."

I turn away from him and start toward the road to see a

Holmes County sheriff's department cruiser glide onto the

shoulder, lights flashing. An ambulance pulls away,

transporting the only survivor to the hospital. Later, the

coroner's office will deal with the dead.

I step over

a chunk of wood from the buggy. The black paint contrasts

sharply against the pale yellow of the naked wood beneath. A

few feet away, I see a little girl's shoe. Farther, a

tattered afghan. Eyeglasses.

This is now a crime

scene. Though the investigation will likely fall under the

jurisdiction of the Holmes County Sheriff's office, I'm

going to do my utmost to stay involved. Rasmussen won't have

a problem with it. Not only will my Amish background be a

plus, but his department, like mine, works on a skeleton

crew, and he'll appreciate all the help he can get.

Now that the injured boy has been transported, any evidence

left behind will need to be preserved and documented. We'll

need to bring in a generator and work lights. If the

sheriff's department doesn't have a deputy trained in

accident reconstruction, we'll request one from the State

Highway Patrol.

I think of Mattie Borntrager, at

home, waiting for her husband and children, and I realize

I'll need to notify her as soon as possible.

I'm on

my way to speak with the paramedics for an update on the

condition of the injured boy when someone calls out my name.

I turn to see my officer, Rupert "Glock" Maddox, approaching

me at a jog. "I got here as quick as I could," he says.

"What happened?"

I tell him what little I know. "The

driver skipped."

"Shit." He looks at the ambulance.

"Any survivors?"

"One," I tell him. "A little boy.

Eight or nine years old."

"He gonna make it?"

"I don't know."

His eyes meet mine and a silent

communication passes between us, a mutual agreement we

arrive upon without uttering a word. When you're a cop in a

small town, you become protective of the citizens you've

been sworn to serve and protect, especially the innocent,

the kids. When something like this happens, you take it

personally. I've known Glock long enough to know that

sentiment runs deep in him, too.

We start toward the intersection, trying to get a sense of

what happened. Delisle Road runs in a north-south direction;

County Road 14 runs east-west with a two-way stop. The speed

limit is fifty-five miles per hour. The area is heavily

wooded and hilly. If you're approaching the intersection

from any direction, it's impossible to see oncoming traffic.

Glock speaks first. "Looks like the buggy was southbound

on Delisle Road."

I nod in agreement. "The second

vehicle was running west on CR 14. Probably at a high rate

of speed. Blew the stop sign. Broadsided the buggy."

His eyes drift toward the intersection. "Fucking T-boned

them."

"Didn't even pause to call nine one one."

He grimaces. "Probably alcohol related."

"Most

hit-and-runs are."

Craning his neck, he eyeballs Andy

Welbaum. "He a witness?"

"First on scene. He's pretty

shaken up." I look past him at the place where the wrecked

buggy lies on its side. "Whatever hit that buggy is going to

have a smashed up front end. I put out a BOLO for an unknown

with damage."

He looks out over the carnage. "Did you

know them, Chief?"

"A long time ago," I tell him.

"I'm going to pick up the bishop and head over to their farm

to notify next of kin. Do me a favor and get Welbaum's

statement, will you?"

"You got it."

I feel his

eyes on me, but I don't meet his gaze. I don't want to share

the mix of emotions inside me at the devastation that's been

brought down on this Amish family. I don't want him to know

the extent of the sadness I feel or my anger toward the

perpetrator.

To my relief, he looks away, lets it go.

"I'd better get to work." He taps his lapel mike. "Call me

if you need anything."

I watch him walk away, then

turn my attention back to the scene. I take in the wreckage

of the buggy. The small pieces of the victims' lives that

are strewn about like trash. And I wonder what kind of

person could do something like this and not stop to render

aid or call for help.

"You better hide good, you son

of a bitch, because I'm coming for you.

Copyright © 2013 by Linda Castillo

Home